Why Wind Shifts Matter More Than You Think

Imagine that you’re lifted and sailing toward a puff. You’re all good, but your luck runs out when you’re headed before you get to the puff. Now you have a dilemma. Should you tack off the header to stay in phase? Or should you ignore the shift and sail through the header to get to the new pressure?

The answer is, “It depends.” It depends on how your boat behaves, how windy it is, and how big the shift is relative to the puff. I approach the decision from the viewpoint of how fast I am going. I’m going slow in light air, so I favor pressure over shift because a good puff could double my speed. I reason it would take a big enough shift to make up for that. I move along nicely in medium winds, but I am not topped out yet. This is the fun range where I need to pick which of the two—shift or pressure—is more significant.

If the puff ahead is large, I would be willing to sail through a small header to get there, but in a big header, I would tack to stay in phase. I’m going fast already in heavy wind, and I figure that I don’t go much faster in a puff, so I focus on the shifts. I consider only the biggest puffs, and even then, only when the shifts are small.

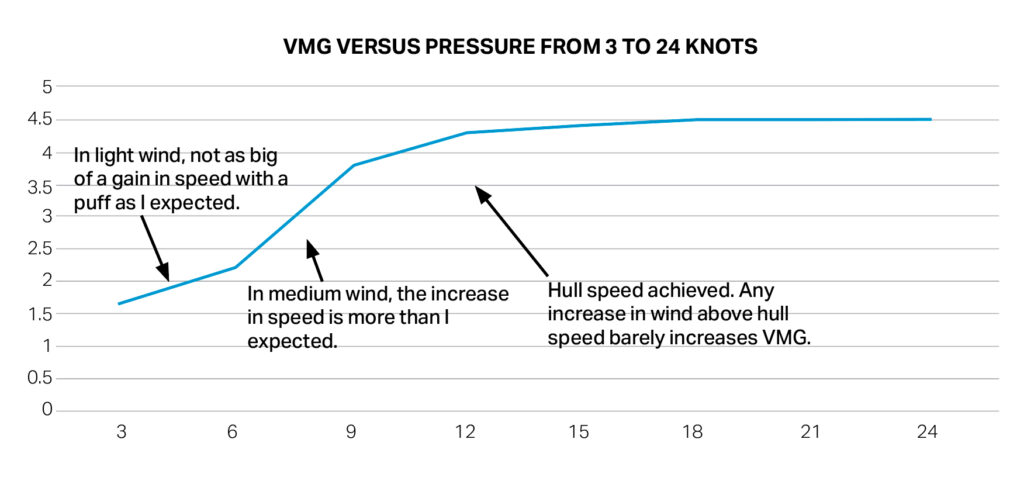

These rules of thumb have served me well, but I wanted to dig deeper into why. I was curious if all my assumptions were right. And what else might I be missing? So, the first thing I did was to use the polars of a popular small one-design keelboat to plot its Velocity Made Good. With this, I can see how the boat’s VMG increased in a puff to see what I can learn. I will layer on shifts later.

VMG versus Pressure from 3 to 24 knots.

Illustration by Kim Downing

VMG versus Pressure from 3 to 24 knots.

Illustration by Kim Downing

Let’s dive into Graph No.1: VMG Versus Pressure. Looking at the VMG Versus Pressure graph, two things surprised me: 1) When it is light (3 to 6 knots), a puff increases VMG less than I expected. I have not layered on shift yet, but my original assumption that I should focus mostly on pressure when it is light is now in question; and 2) above hull speed, there is almost no increase in speed with more pressure. Even with a lot more pressure, the boat will go only so fast. Maybe shifts are not in play as much as I thought, even big ones.

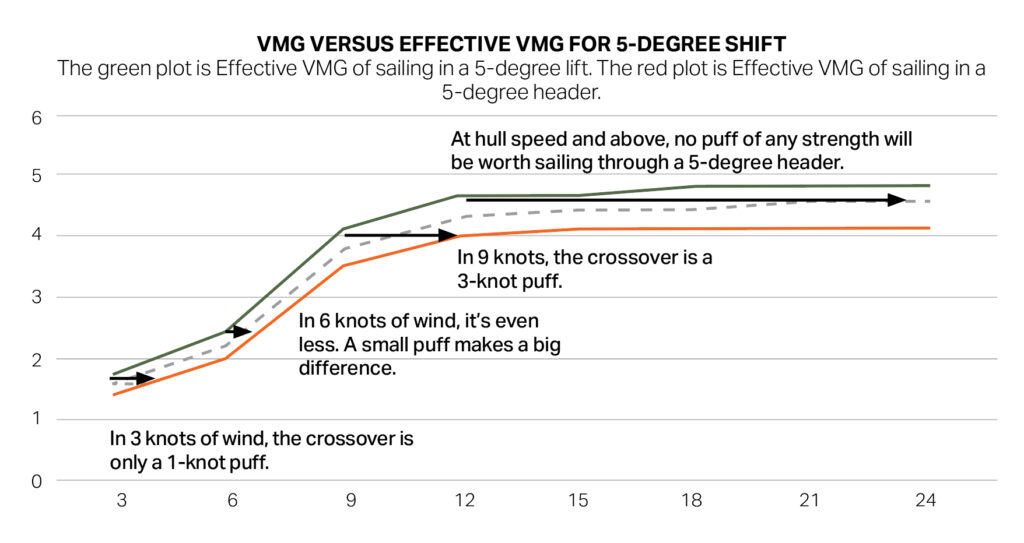

Next, I added a 5-degree shift to our original VMG graph. A lift is just like being able to point higher, increasing our Effective VMG. For example, a 5-degree lift is like pointing at 40 degrees instead of 45. Another thing I realized is that the effect of this shift is doubled because the only alternative to tacking, in order to take advantage of the lift, is to sail the header. The effect is like pointing 5 degrees lower—50 degrees instead of 45. It’s not useful to compare a lift to no shift at all because that’s not an option. To the graph, I added both the increase in Effective VMG by sailing the lift, and the decrease in Effective VMG by sailing the header.

VMG versus Effective VMG for 5-degree shift.

Illustration by Kim Downing

VMG versus Effective VMG for 5-degree shift.

Illustration by Kim Downing

Now consider Graph No. 2, VMG Versus Effective VMG for a 5-Degree Shift. Looking at the Effective VMG of a 5-degree lift versus eating a header is telling. I got it mostly right, but I did learn Lesson No. 3: Shifts become dominant once up to hull speed. There is no amount of puff that will come close to making up for even this relatively small 5-degree shift. At hull speed and above, there is no point in looking for more wind; shifts are all that matter.

The rest fell in line with what I expected, but it’s good to see a number on it to confirm. When the wind is light, it does not take much of a puff to make up for this small shift. When it’s medium, it takes a 3-knot puff, so that too is consistent with my original assumptions that this is a crossover range. But what about a bigger 15-degree shift?

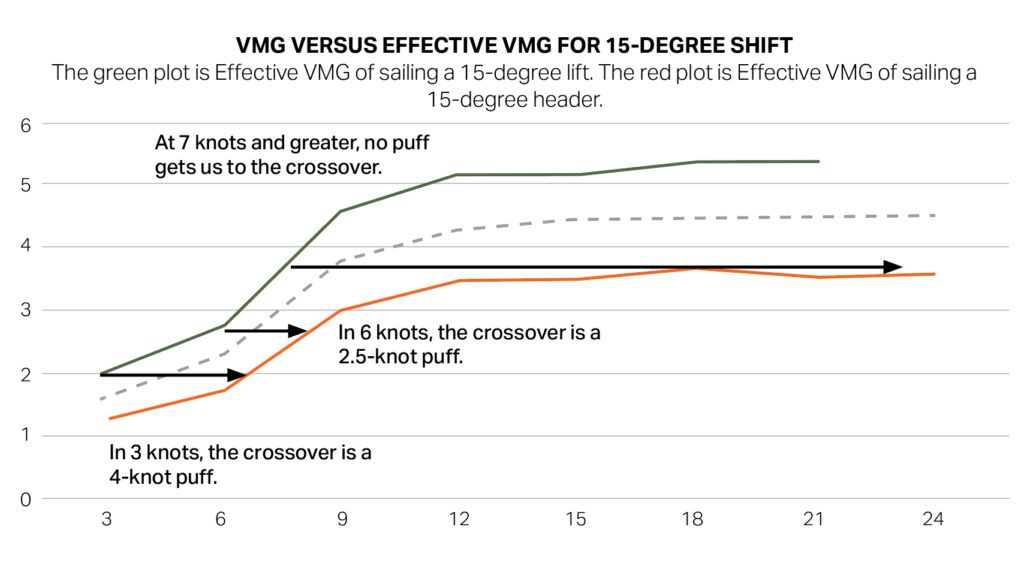

VMG versus Effective VMG for 15-degree shift.

Illustration by Kim Downing

VMG versus Effective VMG for 15-degree shift.

Illustration by Kim Downing

That brings us to Graph No. 3: VMG Versus Effective VMG for 15-Degree Shift. Looking at the impact of a 15-degree shift is equally telling, giving me Lesson No. 4: In light air, both shift and puff are very much in play. I consider a 15-degree shift significant, and in light air, it takes a significant puff to make up for it. Until I did this study, I would still have given any increase in pressure precedence over even this large a shift. And there’s Lesson No. 5: For this boat, when we get to 7 knots, which is well below hull speed, there is no size puff that makes up for a 15-degree shift. A 15-degree shift is significant, but even so, the old me would have given a good-size puff equal consideration. Not anymore.

The graphs are telling, but we are not going to be looking at graphs out on the water, so we need updated rules of thumb.

Light air: Almost any increase in pressure is significantly more important than small shifts. But bigger shifts are a factor and need to be weighed against the size of the puff.

Medium air: When the shifts are small, both shifts and puffs are in play. But if the shifts are big, shifts are all that matter because puffs don’t help enough to be considered.

Heavy air: Shifts are all that matter; even the biggest of puffs cannot make up for a small shift.

I use indicators to quickly figure out what range I am in. Light air is when I am sitting in. Medium air is when I am sitting on the rail or even hiking a little. Heavy air for these purposes is when I reach hull speed. My default is to consider myself at hull speed when I’m fully hiked out. But I fine-tune that by getting to know my boat and what it feels like and how hard I am hiked when it no longer accelerates in a puff. If I’m sailing a boat with a speedo, I simply look at a number.

By focusing on the trade-off between the size of the puff relative to the shift, I have left out one obvious consideration: It also matters how far away the puff is and how long it will last. In our example where we ponder if we should tack to stay in phase or sail a header to the new pressure, if it is far away and short-lived, the answer likely would be to tack. But if it’s just a few boatlengths away and significant, the answer likely would be to suffer through the header for a short time to get to pressure, even if we’ve prioritized shift over puff.

Another factor to consider is that changes in pressure typically bring a different wind direction. We need to anticipate the direction of the shift in the new wind, not just the shift we are sailing in at that moment. Now suppose, in our earlier example, that we think the new wind is a persistent shift. Then likely it is worth sailing the header because when we get there, we can get to more wind and tack onto an even larger lift. That’s a win-win. But if the new wind is likely a lift, that complicates the decision. Layering on that, where we are on the course matters too. If we are getting out to an edge and on the short tack, we might give up on chasing the puff all the way into the corner. But we might justify sailing a header to pressure if it helps center us up on the course.

I wasn’t far off with my original rules of thumb, and I made some nice updates based on this study. Your boat, however, is going to behave a little differently, so you should do a bit of homework. Maybe, for example, your polars show that your boat reacts more to puffs in light wind and less in medium. Your indicators might be different as well. For example, your boat might reach hull speed before you are fully hiked. Or maybe your boat is very different, e.g., it planes or foils upwind. Make the rules of thumb your own based on your boat.

If all you do is prioritize puffs when you are below hull speed and shifts when you are above, that will serve you well. But with your personalized rules of thumb in hand, you’re ready to take it to another level. Prerace while you are tuning, and take a moment to note what wind range you are in, paying particular attention to how much faster (or not) you go in the puffs. Assess how big the shifts and puffs are, and decide which has the biggest impact. Then get a good start on the lifted tack heading for pressure, and you’re all good. If, or when, you get that header, you’re now armed to make the call with confidence.

The post Why Wind Shifts Matter More Than You Think appeared first on Sailing World.

- Home

- About Us

- Write For Us / Submit Content

- Advertising And Affiliates

- Feeds And Syndication

- Contact Us

- Login

- Privacy

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.